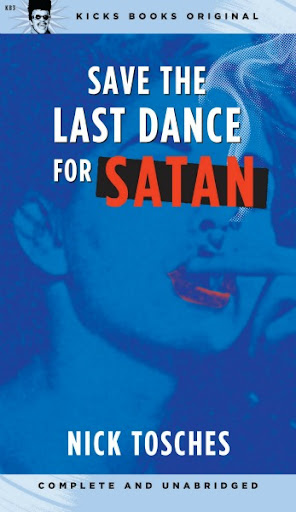

When I first read Nick Tosches, I had no idea who the guy was. I was on a big Dean Martin kick, and picked up Tosches’ hefty biography of the man in my quest to know all things Dino. Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams was like no other celebrity biography I had come across, with a vast scope that put Martin’s whole world in perspective. And, to be honest, I was a little annoyed by it at first. Who was this guy, and why did he keep talking about things other than Martin himself? But I kept reading, all the way to the end, and it left an impression.

Now Nick Tosches is an example to me, an influence, a bit of an idol, and one hell of a beautiful writer. So, when I learned of Tosches’ latest book, Save the Last Dance for Satan, I jumped at the chance to review it for NTSIB (and rope my great friend Rick Saunders into the process).

Satan is published under the auspices of Kicks Books. The book publishing branch of Norton Records (which, in turn, began life as the record label arm of Kicks Magazine, published by Billy Miller and Miriam Linna from 1979 to 1986) was brought into being to keep the great singer Andre Williams occupied with something constructive and rehabilitative while in rehab. When Nick Tosches, who wrote the foreward for Williams’ Sweets and Other Stories, saw the finished product, he contacted Linna about adding a new Tosches title to the growing line-up of Kicks Books.

Tosches’ contribution to Kicks Books is a collection of stories dug out from the underground of early rock ‘n’ roll, a look at the often less-than-above-board way records were recorded and released in the days before the major labels realized they needed to get in on the rock ‘n’ roll racket (and, in turn, institutionalized those less-than-above-board wheelings and dealings). Rick and I sat down and talked about this book full of fascinating characters and sometimes unbelievable true-life tales…

April: So, how much fun was this book?

Rick: Mostly fun. More fun than not. Especially fun for someone like me who’s interested in the old school music industry. I dont know if civilians would dig it but I doubt, like the other titles at Kick Books, that it’s written for them either.

Was it fun for you?

April: It was a blast. It revealed whole worlds within the early music industry that I never knew about and had never even thought about it.

And I dug Tosches’ way of linking things that might seem unconnected at first glance… Though the segue from the Jaynetts to Lee Harvey Oswald had me scratching my head.

Rick: I think the Jaynetts segment was the least interesting for me.I was more interested in the mafia-related stuff. I’d love to read a book about Hy Weiss and the rest of those guys.

If I have a gripe about the book its that it’s just too damn short. It’s like a series of sketches and would have liked to have seem parts of it fleshed out.

For example on page 13, Tosches talks briefly about Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky’s involvement in the juke box biz then on 16 talks about the ban on new music recordings due to James Petrillo’s concern over the “menace of mechanical music” (jukeboxes). I want to know what reaction that got from the mob, etc.

April: Agreed about the Jaynetts segment being the least interesting – which makes me wonder why that seemed to be the lead talking point with all the promos.

Also agreed about the fact that I’d like to see so much of this expanded. I went searching for a biography about Hy Weiss after reading this (and found none – Hey, Nick, I’ve got a book proposal for you…).

The jukebox angle could probably have filled a few chapters on its own. Speaking of, how wonderful was that lead-in? “Coins clinking into the big incandescent Bakelite jukebox. Coins showering to the street from a ninth-story window. Yes, it was a time.” When I read that in the beginning, it evoked one image, but when it came back up again, at the end of the second chapter, it evoked something completely different. It seems like the most perfectly concise description of organized crime’s role in the early rock industry.

Rick: I loved that part. The part where Wassel hangs the DJ out the window. It recalls the story (strictly rumor, Mr. Knight, Sir) of Suge Knight hanging Vanilla Ice out the window to get a piece of the publishing from “Ice Ice Baby”.

“All the change fell out of his pockets. Some friends of mine picked it up.”

April: I love that you thought of that. I didn’t remember that incident well enough to notice the echoes (and I laughed when, later in the book, Toshes mentions a promo man of “the non-defenestrating kind”). It makes you wonder how much of that straight-up “thuggery”, for lack of a better term, goes on now. Or is it all just the widespread, calmly-accepted, this-is-the-way-things-work, “we really believe in our artists” thuggery that the major labels practice every day as a matter of business? …not that I’m cynical at all…

Alan Freed had his reputation severely besmirched in the Payola scandal, but as Freddy DeMann pointed out in the book, it’s not that much different when someone like KROQ puts on their annual holiday show and says, “We want these artists for our show,” with the implication that that label’s singles don’t get played unless the radio station gets their wish-list checked off.

Rick: I tend to take notes on the bookmark whenever i’m reading a book and this book has me doing a lot of further research. I now know what a Gonif is but I gotta know about eggs and sausages being prepared “in exacting and arcane Italianate manners…”

Oh, sure. I see little difference. Certainly less thuggery in the lower echelons among the small labels but once you start playing with the big boys… But artists have a lot more power now than they did in those days.

April: I think it just means “dagos are picky” [Editor’s note: My family’s Italian, so I get to say things like that.]. I loved that phrasing.

The bigger artists have more power, but what about the middling to smaller artists at a big label? Especially now with the opening up of the music market and the panic-stricken practices of the RIAA.

Rick: Hah! Think thats all it is? I hope not. I want some secret society, some Illuminate of Italian chefs passing this egg frying secrets as if they were the masons in their special little aprons.

April: Heehee! Though that leads into possibly my favorite thing about this book: the way Tosches often just sits back and lets the players talk. The way he illustrates his meetings with these guys, sitting around a table, eating and shooting the shit, and then just letting them talk. I did feel a little nostalgic for after-dinner conversation with my extended family. Tosches captured that rhythm of sitting around the table, telling stories so well.

Rick: He really does. The parts with Weiss and Wassell, and the parts with Jerry Blavatz were terrific jest because of that.

Another thing I want to look in to is Benny Goodman’s brothers who allegedly withheld royalties from The Fiestas.

There was a similar situation with the brothers in the Howlin’ Wolf bio Moanin’ at Midnight where they took advantage of Wolf and his lack of business acumen.

April: Those Goodman brothers seem like bad news.

Rick: Wolf’s wife, as I recall, eventually sued and won. She didn’t have to resort to threatening to slice a Goodman’s throat with a broken Coke bottle like in Tosches’ book.

April: Ha! Good for her.

Taken on its own, what was your favorite story from the book?

Rick: Favorite story… tough call. I’d say the stuff about Hy Weiss and Wassel. But that part is so short.

The stories about Jerry Blavatz is more satisfying. But really it comes down to Tosches writing. His comment about The Beatles being “sort of a silly girl group with male genitals” killed me. Few books make me laugh out loud. His reference to Dick Clark as a “cultural hygienist” slayed me. Clark’s another guy i’d like to read more about.

April: Love love love the Beatles line.

Rick: You mention payola. Clark was questioned and denied everything. Freed was screwed by his personality and attitude.

And what was your favorite story?

And would you recommend Save The Last Dance For Satan to friends?

April: The bit about Clark taking everything was very telling… and pretty unsurprising, really.

My favorite story, aside from just the entirety of Weiss and Wassel, as you say, was the bit about the record label front set up in the Brill Building that turned into an actual record label after Maxine Brown walked in the door and launched the front into becoming more lucrative than the racket it was covering up. It’s such a tidy, poetic little turn of events.

Would I recommend it to friends? Well, I’d recommend it to you, but that’s cheating.

I think anyone whose curiosity is even a little piqued by the idea of the book should not hesitate in checking it out, and there are so many angles that could pique a curiosity – the music business angle, the organized crime angle, the Jack Ruby story, the Alan Freed story. And I might add to the people who have been frightened off from Tosches by his byzantine word choices that I only had to touch my dictionary twice while reading this.

What do you think? Would you recommend it?

Rick: I would but to the same people as you, those with an interest in the music industry or who might want to check out Tosches in small bites. I think it’s too bad if there are people scared off by his word choices, I think it’s brilliant. Those are my favorite kinds of books. I think it’s a terrific book which may not have come off in my earlier comments but I must say that I reread about 1/2 of it last night knowing we were going to talk about it today and I plan to finish re-reading it. In spite of any gripes I may have about it it’s a thoroughly enjoyable and at times enthralling little book. I like books that lead me to other places/subjects/people after reading them and this work has certainly done that.

April: Agreed, and I think that’s something Tosches has a talent for: leading one to other places, to seek more knowledge. He really is just an incredibly good, adept writer, no matter which way he turns his hand, toward the simple or toward the ornate.